SELF-HELP

Look, See: Maia Horta’s Little Acts of Voyeurism by Ruth Rosengarten

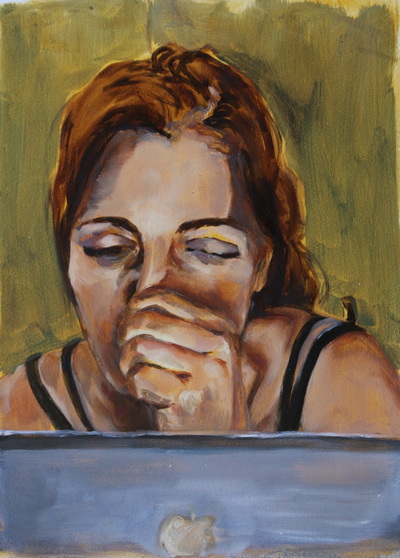

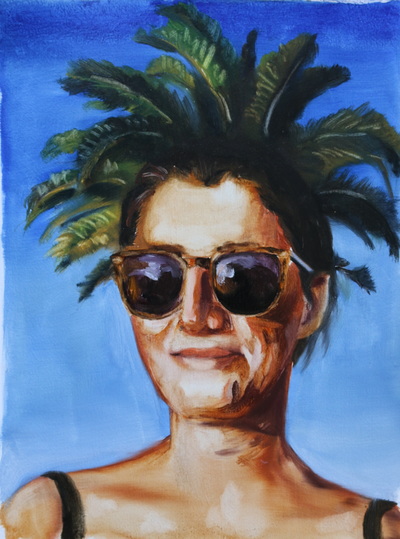

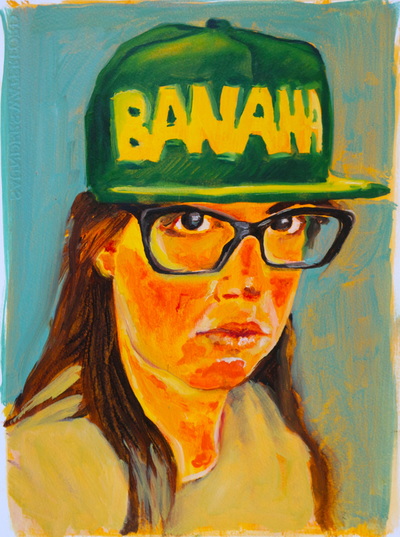

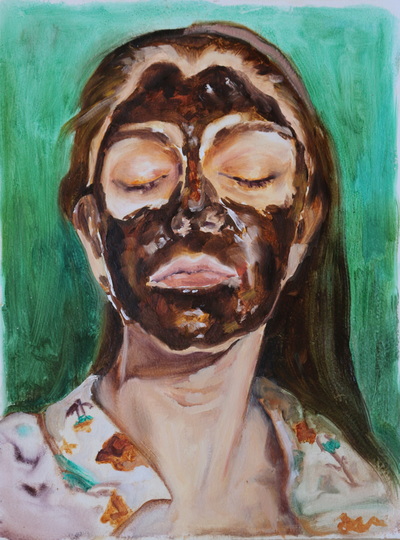

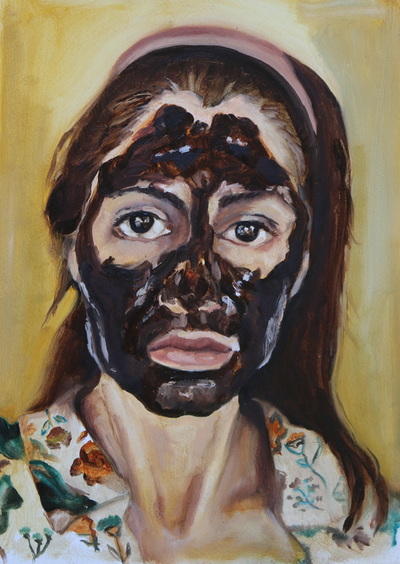

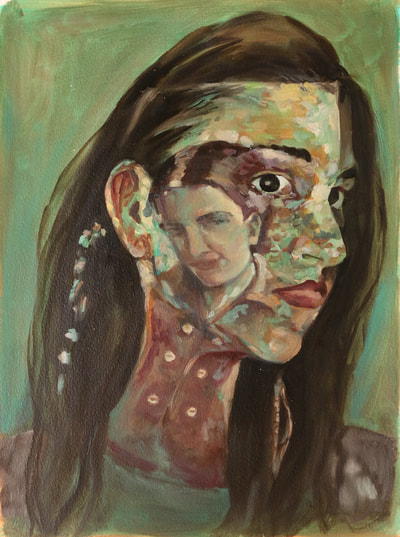

Maia Horta posts selfies on Facebook. There’s nothing unusual about that, except for the fact that in her selfies, Maia doesn’t project her ‘best’ (most photogenic) face; does not perform the most glamorous, popular ‘self’ that is so often implicit in the trope of the ‘selfie.’ Rather, we see an array of invented personas that, whether photographed or painted, are charged with painterly conventions. But equally striking is the fact that in Maia’s staging of self, facial hair plays a big part: beards, moustaches, lashes that rim the lips in provocative simulacrum of vulvas. And if this were not enough to make one think of the morphological analogies between faces and genitals, Maia often underlines that upper orifice by stuffing something into it (banana, cigarette), or sticking something out of it (bubble gum, tongue.) Not so much an allusion to oral sex, it is as if the whole act of coitus were shamelessly performed upon another bodily stage.

These preoccupations with the visible markers of gender identity – with the making visible of polymorphous gender identity – are rehearsed and reiterated in Maia’s paintings, which concern themselves with the relationship between looking at art and looking at bodies, and in particular, looking at naked female bodies. In this, she partakes of a powerful lineage of feminist artists.

Full Essay:

Look, See: Maia Horta’s Little Acts of Voyeurism

Maia Horta posts selfies on Facebook. There’s nothing unusual about that, except for the fact that in her selfies, Maia doesn’t project her ‘best’ (most photogenic) face; does not perform the most glamorous, popular ‘self’ that is so often implicit in the trope of the ‘selfie.’ Rather, we see an array of invented personas that, whether photographed or painted, are charged with painterly conventions. But equally striking is the fact that in Maia’s staging of self, facial hair plays a big part: beards, moustaches, lashes that rim the lips in provocative simulacrum of vulvas. And if this were not enough to make one think of the morphological analogies between faces and genitals, Maia often underlines that upper orifice by stuffing something into it (banana, cigarette), or sticking something out of it (bubble gum, tongue.) Not so much an allusion to oral sex, it is as if the whole act of coitus were shamelessly performed upon another bodily stage.

These preoccupations with the visible markers of gender identity – with the making visible of polymorphous gender identity – are rehearsed and reiterated in Maia’s paintings, which concern themselves with the relationship between looking at art and looking at bodies, and in particular, looking at naked female bodies. Of course in this, she partakes of a powerful lineage of feminist artists. Since the late 1960s, makers of art in this lineage have explored the metaphors that are issued by the naked female form, and the particular evasions (from fig-leaf, through coy hand or drapery, to depilation, literally shaving away the evidence of messy under-parts) surrounding female genitalia. The relationship between the vagina and disgust – a relationship that is implicit in so much visual culture – has always been at the heart of these critical works.

For centuries, naked male bodies (from the Greek kouros on) tended to armour-like containment; women’s were soft, undulating, and owned this cut place that was neither fully internal, nor entirely external, a rupture. This is how art historian Lynda Nead put it: ‘If the female body is defined as lacking containment and issuing filth and pollution from its faltering outlines and broken surface, then the classical forms of art perform a kind of magical regulation of the female body, containing it and momentarily repairing the orifices and tears.’ Historically, with male artists as the predominant actors in the field and, until the twentieth century, men as the presumed or idealised spectators, the female nude became the space of regulation by culture over nature, and ways of papering over that orifice revealed the overriding power of culture over nature, materialised as the mastery of the male gaze over the female body.

Simultaneously, however, the female nude offered the ultimate titillation by providing spectators with a glimpse of the site of prohibited viewing, a small prospect of big danger, of which the notion of the vagina dentata was merely the hyperbole. And when such male artists (from Courbet through Picasso and Dubuffet to de Kooning and, with greater theoretical knowingness, Marcel Duchamp) began prising open women’s legs, exposing the concealed, bringing the inside out into the open, metaphors spilled out: for Courbet, the cunt was nothing short of ‘the origin of the world’ itself, exposing how easy the oscillation between revilement and idealisation. It was when feminist artists, and in particular performance artists (Shigeko Kubota’s Vagina Painting of 1965, Valie Export’s Genital Panic of 1969 and Carolee Schneeman’s Interior Scroll of 1976) began to explore the vagina as a site not of (Freudian) lack, but of confrontation and creativity – breaking the mould that identifies seeing and making with masculinity and being seen and posing with femininity – that the sexual politics of vision came to be more fully exposed, so to speak, and explored. It was also no coincidence that such feminist performances prioritised touch over sight, since historically, sight has been so burdened with male agency.

Rather than eschewing a relationship with the gaze, Maia throws herself into the arena and explores it, explores, not least, the possible collusion of women in the binary structure of the scopic regime: in John Berger’s famous equation, men act and women appear. What Maia’s works bring into the equation is a curiosity about Berger’s formulation; a curiosity, in short, about the relationship between such historically and ideologically freighted occlusions and displays, and that other form of viewing, generally considered more benign: the gaze that is enlisted in the production of art. An art that addresses itself to the eyes, and that, in some ways like pornography, produces pleasure. Maia explores the ways in which curiosity and pleasure are intrinsically entailed in a scopic regime that underlies not only the production of art, but also its circuits, the passage from studio to the marketplace, from marketplace to museum, where nicely dressed women and men peer earnestly at the strip-tease of women’s bodies.

It is perhaps no coincidence that two of her exhibitions have taken place within the small, exposed stage of a shop window, that traditional site of display and temptation, where desire and consumption are played off against each other within the embracing parameters of a capitalist economy. The artist described Art Lovers, shown at the Soapbox Gallery in Brooklyn, New York (2012), as a ‘voyeuristic experience of sorts.’ It consisted of a series of small oil paintings hung in random grid formation within the shallow area of the gallery window. Interspersed with portraits of female literary [ maia, were they all literary?] icons such as Virginia Woolf and Sylvia Plath, were images in which the act of looking (at art) is the pictorial event that we (spectators) watch. In each painting, a viewer seen from the back is portrayed regarding a well-known work of art in which a female nude explicitly displays herself to the spectator’s gaze. As secondary viewers, we are enlisted to witness these acts of witnessing in a motion of identification with the viewing figures in the pictures. That these viewers are both male and female highlights the extent to which women spectators are recruited to occupy and collude with the position of desire traditionally associated with the (heterosexual) male spectator.

The small scale of the works, while presenting practical advantages to the artist (she transported them to New York in a suitcase), also served to invite viewers of the exhibition to closer examination. This invitation was, however, frustrated by the transparent pane of the shop window through which the works were seen, teasing the viewer into a proximity that is visual, but not tactile. In this way, the theme of the exhibition was replicated and refracted by its form: titillation, invitation, frustration.

In these paintings of ‘art lovers’ peering directly into the offering revealed by women’s parted thighs, the allusions to existing works of art multiply: so we have Gerhard Richter’s ‘Betty’ looking at a menstruating girl from a Pipilotti Rist photographic print; a male figure lifted from a painting by Belgian artist Michäel Borremans gazing at Duchamp’s Étant Donnés, or another figure from Borremans, this time a woman, peeping into the cunt displayed in a painting by Lisa Yuscavage. In Happy Wife, Happy Life (2012), a drawing by Swedish artist Jockum Nordstrom is being looked at by a figure from a painting by his wife, Mamma Andersson. And in Origin of the World, a female spectator resembling Maia herself watches a video by Pipilotti Rist, which in turn references Courbet’s provocative Origin of the World. Photographers at the Museum (2011) and Babes at the Museum (2011) both gently satirise the appropriative and mimetic behaviour of museum visitors performing the act of looking. All these small paintings are rendered in a consciously awkward, deadpan style that references the art-historical painting academy more than it does the trendy idioms of electronic media. Maia’s paintings enter into a stylistic conversation with a loose group of painters that includes John Currin, Mamma Andersson, Marlene Dumas, Lisa Yuscavage, Michael Borremans, artists who more or less explicitly probe the boundaries between high art and more vernacular (or even kitsch) styles and sentiments.

In the series Posh Lust that followed Art Lovers, Maia focussed more closely on forging links or contiguities between the displayed nude in western art, and the commercial circuits that lead from studio to auction house, circuits that run between private and public spaces. If the studio is traditionally a place of solitary activity and possible poverty, the auction house is a location of ‘posh lust’, where desire (the desire to own works of art) is dressed in very expensive clothes. These are small oil paintings on gessoed paper: a dry, close-pored, matt surface. The formats are panoramic, the handling is looser, brushier, more evocative than in the previous series. The works are packed with art historical allusion, in the forms of paintings at auction houses: in She Works Hard for the Money, Manet’s Olympia (a work that, it is fair to say, is unlikely to ever enter the auction house again) vies with works by Georgia O’Keefe and Dürer: both the Manet and the Dürer are iconic works in feminist theorisation of the scopic regime entailed in the display of the female nude to the male gaze in five centuries of western painting. In How Come You Never Go There, Gerhard Richter meets Boucher, while in Some Like it Hot, the artist focuses on headless, splayed nudes by Rodin and Duchamp.

Underpinning the project is a conceptual framework that harnesses Maia’s readings around the art market (with special focus now on the auction house and on gender discrepancy in sales of art) to her ticklish fascination with image appropriation on the one hand, and with the extent to which the eroticised female body adds value to works of art on the other. The series was granted further consistency by the fact that the titles were borrowed from popular songs to which Maia listens while painting, bringing to the completed works an allusion to the process of their production in the studio. The full cycle, from studio work to commercial circuits, is thus covered in these tiny works.

In Valise (2013), the artist reprises all her themes and concerns, with a knowing wink at Duchamp’s Boîte en Valise, in which the celebrated dada anti-artist vexed the conditions of ‘original’ and ‘reproduction’ that are so essential to the positioning of a work within the system of the art market. Duchamp’s miniaturisation of his entire corpus into a deluxe edition of photographic reproductions, served – like a travelling salesman’s valise – as a showcase, and for the ‘artist’, that showcase became a portable museum. In this, Duchamp operated a sly critique, both of coherent artistic (monographic) identity and of the development of photographic reproduction in the service of the archival systematisation of works of art.

Maia’s Valise too is a compendium of her previous works, each reproduced on a matchbox, thus paying homage to Duchamp as conceptual precedent. Like Duchamp’s valise, Maia’s allow us to explore the notion of scopic control facilitated by the miniature, and the illusory satisfaction it produces, the satisfaction of complete knowledge. One glimpse affords us an entire body of work: in the context of quick consumption that characterises our times, what could be more apparently satisfying? With her customary wry humour, Maia gathers together diverse cultural references entailed in the object ‘matchbox’ (and that includes Hans Christian Anderson’s story ‘The Little Match-Seller’ and Aki Kaurismaki’s film The Match Factory Girl), while ironically allowing that the low-value matchbox reproductions of her works might serve as ‘souvenirs for the fans.’ In this, as in Art Lovers and Posh Lust, Maia implicitly but relentlessly pits the notion of market value against the subjective, personal value with which individual viewers invest works of art, whether in the original or in reproduction.

In Maia Horta’s production of works outside of the studio, whether collaboratively or in the social media, there is an impish, derisory wish to explode and undermine not only gendered expectations and viewing conventions, but also the market conditions that facilitate and sponsor these positions. But, significantly, in her studio practice, the artist remains faithful to the traditional medium of painting in order to probe the structures – at once spectatorial and commercial – that sustain the value of painting in the marketplace.

Ruth Rosengarten © 2014

Maia Horta posts selfies on Facebook. There’s nothing unusual about that, except for the fact that in her selfies, Maia doesn’t project her ‘best’ (most photogenic) face; does not perform the most glamorous, popular ‘self’ that is so often implicit in the trope of the ‘selfie.’ Rather, we see an array of invented personas that, whether photographed or painted, are charged with painterly conventions. But equally striking is the fact that in Maia’s staging of self, facial hair plays a big part: beards, moustaches, lashes that rim the lips in provocative simulacrum of vulvas. And if this were not enough to make one think of the morphological analogies between faces and genitals, Maia often underlines that upper orifice by stuffing something into it (banana, cigarette), or sticking something out of it (bubble gum, tongue.) Not so much an allusion to oral sex, it is as if the whole act of coitus were shamelessly performed upon another bodily stage.

These preoccupations with the visible markers of gender identity – with the making visible of polymorphous gender identity – are rehearsed and reiterated in Maia’s paintings, which concern themselves with the relationship between looking at art and looking at bodies, and in particular, looking at naked female bodies. In this, she partakes of a powerful lineage of feminist artists.

Full Essay:

Look, See: Maia Horta’s Little Acts of Voyeurism

Maia Horta posts selfies on Facebook. There’s nothing unusual about that, except for the fact that in her selfies, Maia doesn’t project her ‘best’ (most photogenic) face; does not perform the most glamorous, popular ‘self’ that is so often implicit in the trope of the ‘selfie.’ Rather, we see an array of invented personas that, whether photographed or painted, are charged with painterly conventions. But equally striking is the fact that in Maia’s staging of self, facial hair plays a big part: beards, moustaches, lashes that rim the lips in provocative simulacrum of vulvas. And if this were not enough to make one think of the morphological analogies between faces and genitals, Maia often underlines that upper orifice by stuffing something into it (banana, cigarette), or sticking something out of it (bubble gum, tongue.) Not so much an allusion to oral sex, it is as if the whole act of coitus were shamelessly performed upon another bodily stage.

These preoccupations with the visible markers of gender identity – with the making visible of polymorphous gender identity – are rehearsed and reiterated in Maia’s paintings, which concern themselves with the relationship between looking at art and looking at bodies, and in particular, looking at naked female bodies. Of course in this, she partakes of a powerful lineage of feminist artists. Since the late 1960s, makers of art in this lineage have explored the metaphors that are issued by the naked female form, and the particular evasions (from fig-leaf, through coy hand or drapery, to depilation, literally shaving away the evidence of messy under-parts) surrounding female genitalia. The relationship between the vagina and disgust – a relationship that is implicit in so much visual culture – has always been at the heart of these critical works.

For centuries, naked male bodies (from the Greek kouros on) tended to armour-like containment; women’s were soft, undulating, and owned this cut place that was neither fully internal, nor entirely external, a rupture. This is how art historian Lynda Nead put it: ‘If the female body is defined as lacking containment and issuing filth and pollution from its faltering outlines and broken surface, then the classical forms of art perform a kind of magical regulation of the female body, containing it and momentarily repairing the orifices and tears.’ Historically, with male artists as the predominant actors in the field and, until the twentieth century, men as the presumed or idealised spectators, the female nude became the space of regulation by culture over nature, and ways of papering over that orifice revealed the overriding power of culture over nature, materialised as the mastery of the male gaze over the female body.

Simultaneously, however, the female nude offered the ultimate titillation by providing spectators with a glimpse of the site of prohibited viewing, a small prospect of big danger, of which the notion of the vagina dentata was merely the hyperbole. And when such male artists (from Courbet through Picasso and Dubuffet to de Kooning and, with greater theoretical knowingness, Marcel Duchamp) began prising open women’s legs, exposing the concealed, bringing the inside out into the open, metaphors spilled out: for Courbet, the cunt was nothing short of ‘the origin of the world’ itself, exposing how easy the oscillation between revilement and idealisation. It was when feminist artists, and in particular performance artists (Shigeko Kubota’s Vagina Painting of 1965, Valie Export’s Genital Panic of 1969 and Carolee Schneeman’s Interior Scroll of 1976) began to explore the vagina as a site not of (Freudian) lack, but of confrontation and creativity – breaking the mould that identifies seeing and making with masculinity and being seen and posing with femininity – that the sexual politics of vision came to be more fully exposed, so to speak, and explored. It was also no coincidence that such feminist performances prioritised touch over sight, since historically, sight has been so burdened with male agency.

Rather than eschewing a relationship with the gaze, Maia throws herself into the arena and explores it, explores, not least, the possible collusion of women in the binary structure of the scopic regime: in John Berger’s famous equation, men act and women appear. What Maia’s works bring into the equation is a curiosity about Berger’s formulation; a curiosity, in short, about the relationship between such historically and ideologically freighted occlusions and displays, and that other form of viewing, generally considered more benign: the gaze that is enlisted in the production of art. An art that addresses itself to the eyes, and that, in some ways like pornography, produces pleasure. Maia explores the ways in which curiosity and pleasure are intrinsically entailed in a scopic regime that underlies not only the production of art, but also its circuits, the passage from studio to the marketplace, from marketplace to museum, where nicely dressed women and men peer earnestly at the strip-tease of women’s bodies.

It is perhaps no coincidence that two of her exhibitions have taken place within the small, exposed stage of a shop window, that traditional site of display and temptation, where desire and consumption are played off against each other within the embracing parameters of a capitalist economy. The artist described Art Lovers, shown at the Soapbox Gallery in Brooklyn, New York (2012), as a ‘voyeuristic experience of sorts.’ It consisted of a series of small oil paintings hung in random grid formation within the shallow area of the gallery window. Interspersed with portraits of female literary [ maia, were they all literary?] icons such as Virginia Woolf and Sylvia Plath, were images in which the act of looking (at art) is the pictorial event that we (spectators) watch. In each painting, a viewer seen from the back is portrayed regarding a well-known work of art in which a female nude explicitly displays herself to the spectator’s gaze. As secondary viewers, we are enlisted to witness these acts of witnessing in a motion of identification with the viewing figures in the pictures. That these viewers are both male and female highlights the extent to which women spectators are recruited to occupy and collude with the position of desire traditionally associated with the (heterosexual) male spectator.

The small scale of the works, while presenting practical advantages to the artist (she transported them to New York in a suitcase), also served to invite viewers of the exhibition to closer examination. This invitation was, however, frustrated by the transparent pane of the shop window through which the works were seen, teasing the viewer into a proximity that is visual, but not tactile. In this way, the theme of the exhibition was replicated and refracted by its form: titillation, invitation, frustration.

In these paintings of ‘art lovers’ peering directly into the offering revealed by women’s parted thighs, the allusions to existing works of art multiply: so we have Gerhard Richter’s ‘Betty’ looking at a menstruating girl from a Pipilotti Rist photographic print; a male figure lifted from a painting by Belgian artist Michäel Borremans gazing at Duchamp’s Étant Donnés, or another figure from Borremans, this time a woman, peeping into the cunt displayed in a painting by Lisa Yuscavage. In Happy Wife, Happy Life (2012), a drawing by Swedish artist Jockum Nordstrom is being looked at by a figure from a painting by his wife, Mamma Andersson. And in Origin of the World, a female spectator resembling Maia herself watches a video by Pipilotti Rist, which in turn references Courbet’s provocative Origin of the World. Photographers at the Museum (2011) and Babes at the Museum (2011) both gently satirise the appropriative and mimetic behaviour of museum visitors performing the act of looking. All these small paintings are rendered in a consciously awkward, deadpan style that references the art-historical painting academy more than it does the trendy idioms of electronic media. Maia’s paintings enter into a stylistic conversation with a loose group of painters that includes John Currin, Mamma Andersson, Marlene Dumas, Lisa Yuscavage, Michael Borremans, artists who more or less explicitly probe the boundaries between high art and more vernacular (or even kitsch) styles and sentiments.

In the series Posh Lust that followed Art Lovers, Maia focussed more closely on forging links or contiguities between the displayed nude in western art, and the commercial circuits that lead from studio to auction house, circuits that run between private and public spaces. If the studio is traditionally a place of solitary activity and possible poverty, the auction house is a location of ‘posh lust’, where desire (the desire to own works of art) is dressed in very expensive clothes. These are small oil paintings on gessoed paper: a dry, close-pored, matt surface. The formats are panoramic, the handling is looser, brushier, more evocative than in the previous series. The works are packed with art historical allusion, in the forms of paintings at auction houses: in She Works Hard for the Money, Manet’s Olympia (a work that, it is fair to say, is unlikely to ever enter the auction house again) vies with works by Georgia O’Keefe and Dürer: both the Manet and the Dürer are iconic works in feminist theorisation of the scopic regime entailed in the display of the female nude to the male gaze in five centuries of western painting. In How Come You Never Go There, Gerhard Richter meets Boucher, while in Some Like it Hot, the artist focuses on headless, splayed nudes by Rodin and Duchamp.

Underpinning the project is a conceptual framework that harnesses Maia’s readings around the art market (with special focus now on the auction house and on gender discrepancy in sales of art) to her ticklish fascination with image appropriation on the one hand, and with the extent to which the eroticised female body adds value to works of art on the other. The series was granted further consistency by the fact that the titles were borrowed from popular songs to which Maia listens while painting, bringing to the completed works an allusion to the process of their production in the studio. The full cycle, from studio work to commercial circuits, is thus covered in these tiny works.

In Valise (2013), the artist reprises all her themes and concerns, with a knowing wink at Duchamp’s Boîte en Valise, in which the celebrated dada anti-artist vexed the conditions of ‘original’ and ‘reproduction’ that are so essential to the positioning of a work within the system of the art market. Duchamp’s miniaturisation of his entire corpus into a deluxe edition of photographic reproductions, served – like a travelling salesman’s valise – as a showcase, and for the ‘artist’, that showcase became a portable museum. In this, Duchamp operated a sly critique, both of coherent artistic (monographic) identity and of the development of photographic reproduction in the service of the archival systematisation of works of art.

Maia’s Valise too is a compendium of her previous works, each reproduced on a matchbox, thus paying homage to Duchamp as conceptual precedent. Like Duchamp’s valise, Maia’s allow us to explore the notion of scopic control facilitated by the miniature, and the illusory satisfaction it produces, the satisfaction of complete knowledge. One glimpse affords us an entire body of work: in the context of quick consumption that characterises our times, what could be more apparently satisfying? With her customary wry humour, Maia gathers together diverse cultural references entailed in the object ‘matchbox’ (and that includes Hans Christian Anderson’s story ‘The Little Match-Seller’ and Aki Kaurismaki’s film The Match Factory Girl), while ironically allowing that the low-value matchbox reproductions of her works might serve as ‘souvenirs for the fans.’ In this, as in Art Lovers and Posh Lust, Maia implicitly but relentlessly pits the notion of market value against the subjective, personal value with which individual viewers invest works of art, whether in the original or in reproduction.

In Maia Horta’s production of works outside of the studio, whether collaboratively or in the social media, there is an impish, derisory wish to explode and undermine not only gendered expectations and viewing conventions, but also the market conditions that facilitate and sponsor these positions. But, significantly, in her studio practice, the artist remains faithful to the traditional medium of painting in order to probe the structures – at once spectatorial and commercial – that sustain the value of painting in the marketplace.

Ruth Rosengarten © 2014